The European Union realises that innovation is vital to maintain

competitiveness in the global economy. Therefore, the EU is investing in

policies and programmes that support the development of innovation to better

convert research into improved goods, services or processes for the market. Some

examples, Europe supports the development of innovation in priority areas

through the H2020 programme and fosters the commercialisation of innovation

through Public Procurement and Demand-Side Policies. It also monitors

innovation performance through the European Innovation Scoreboards at a

national and regional levels to identify where policy updates may be required. At

a UK level, the UK Research and Innovation body brings together 7 Research

Councils, Innovate UK and Research England to create the best possible

environment for innovation to flourish. Innovation is also supported at a

regional level. In North Yorkshire for example, the Biorenewables Development

Centre offers support to local SMEs for the scale-up of their innovation

through ERDF funding.

With multiple policies and innovation support programmes

across different EU countries and regions, it may be necessary to take a step

back and ask ourselves ‘what does the term innovation really mean? Innovation has been described in many ways; for example, as a new

creation of economic significance which can be formed by new elements or a

combination of existing elements. According to the European Commission,

innovation is the use of new ideas, products or methods where they have not

been used before.

However, despite all the initiatives supporting innovation, not

all promising ideas reach the market. What characterises a successful

innovation then? Are there any red flags that indicate a potential innovation’s

failure?

In the 80’s many people asked themselves these very same

questions attempting to understand the competitive advantage that Japan had won

over the US and Europe. Experts realised that the success of a specific idea

depended on many factors which, among others, include the organisations working

around a specific innovation, how these organisations interact with each other

and the policies surrounding the innovation which may help drive or hinder the

idea. Experts also realised that to be able to understand and even influence an

innovation process, it was necessary to study all the factors surrounding an

innovation, later labelled the Innovation

System. Chris Freeman, an academic at the University of Sussex studying

innovation, defined ‘Innovation Systems’ as the network of institutions in the

public and private sectors whose activities and interactions initiate, import,

modify and diffuse new technologies. The innovation system approach diffused

rapidly as it gave policy makers the necessary tools to compare different

innovation support methods.

Innovation systems can be analysed to understand its

strengths and potential red flags. Marko Hekkert from the University of Utrecht

put together a guide to help policy makers with the analysis of technology

innovation systems. Prior to the analysis, it is important to define the

boundaries of the innovation system including whether the object of analysis

will be a product/technology or knowledge field, or a region or nation. This allows

to differentiate between several types of innovation systems such as National or Regional Innovation Systems, which aim to understand a nation or

region’s innovation performance; a Sectoral

Innovation System which focuses on the assessment of a specific industrial

sector; and Technological Innovation Systems which circle around certain technological development.

According to Hekkert’s guide, the analytical process starts with

a structural analysis. This exercise

should provide info about the elements that comprise the system, including key

organisations, the relations among them and the rules that shape these

interactions. Any organisation that interacts with the innovation under study

is known as an actor of the innovation

system. Actors may include government bodies, knowledge institutes,

educational organisations and industry among others. Similarly, the rules that

shape interactions between actors are known as institutions of the innovation system. Institutions can be

classified as formal, those designed and enforced by an authority, and informal

which are shaped by human interactions (i.e. social norms, beliefs).

If we look at an innovation system as a set of building

blocks that you would like to use to construct something, defining the

boundaries of your innovation would be equivalent to decide what you are going

to build, its size and the purpose of the construction. Similarly,

understanding the structure of your system would be equivalent to get

familiarised with the type of blocks you have, the compatibilities between the

different blocks and the rules you are going to follow for your construction.

It is important to remember that the structural analysis of the

innovation system is not enough on its own to fully comprehend the complexity

of an innovation system, as systems with similar structures may function in

completely different ways if, for example, they are based in different

countries where different social norms or beliefs apply. In consequence, an

analysis of the activities carried out by the actors of the system is also

necessary. In an innovation system, these activities are generally called

functions. So, what are the key functions

of an innovation system?

Marko Hekkert defined seven main functions for the analysis

of a Technological Innovation System. These functions include the role of

entrepreneurs (1), who take ideas into actions and therefore reduce the

uncertainty about a specific technology. Other key functions of an innovation

system are knowledge development (2) and diffusion (3); understanding the key

research and development efforts being made towards a specific innovation, as

well as how the generated info flows between the actors involved is very

important. The functions of guidance on search (4) and resource mobilisation (5)

focus on resources; the former includes the activities in place (i.e.

incentives and pressures) to guide the use of resources towards a common

direction; the later analyses the potential of your innovation to mobilise a

series of resources. The last two functions, market formation (6) and

counteracting resistance to change (7), are related to the type of market

available for the innovation under study, and the mechanisms in place for the

innovation to be legitimated and accepted by consumers respectively.

The structural and functional analyses allowed us to

understand ‘how’ the system works. Now

we need to go a step further to learn how well the system functions. How do we

assess the ‘how well’?

We need to pay attention to the influence that each function

has over the other functions, to understand whether functions reinforce each

other, creating a positive or virtuous cycle loop, or on the contrary some

functions weaken the impact of other functions. It is important to realise that

the stage of development of an

innovation system will affect the dynamics of the system, and therefore

efforts should also be put towards determining the stage of development of the

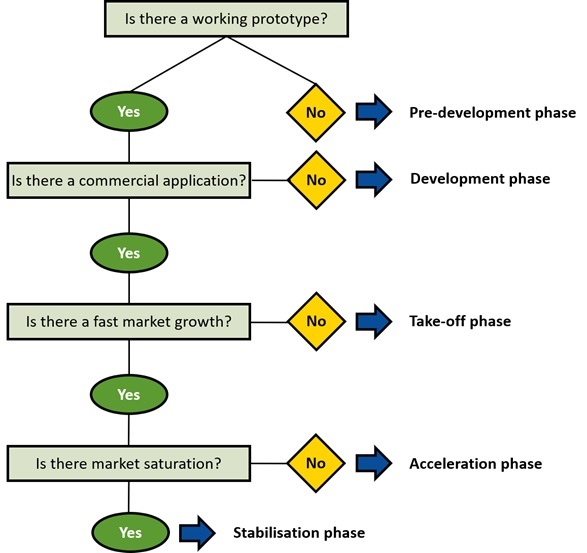

innovation. In his guide, Marko Hekkert provided some diagnostic questions to

help with this. For example, is there a

working prototype? This will help establishing whether the innovation is at

a ‘pre-development stage’ or has, instead, reached the ‘development phase’. The

question is there commercial application? would help determining whether the transition to ‘take-off phase’ has occurred. Is there a fast-growing market? would

let us know if the innovation has reached the ‘acceleration stage’. At the formative or developmental phase all

functions can be critical, being entrepreneurial activities the most important

function at this stage. In later stages such as the take-off phase, entrepreneurial activities are still critical, but

their purpose has shifted from gathering info about the technology to legitimation

of the innovation. In the take-off phase, however, knowledge functions are not as

relevant anymore as plenty of information about the innovation has been

gathered in previous phases. Finally, during the acceleration phase of the innovation, the formation of a market for

the innovation becomes the priority function.

Figure 1: Diagnostic questions to determine the phase of development of an innovation

system.

By understanding ‘how

well’ a system works, we are making ourselves aware of any functions that

may be hampering the development of the innovation. This type of knowledge

about a system is critical as it can be used to remedy the problem hindering

the innovation’s development. The identified hampering function is generally

associated to a structural problem, and therefore it becomes necessary to find

out which structural component is the source of the issue.

Finally, it is important to understand whether the relevant policies

in place are capable of tackling the structural and functional barriers

identified, and to achieve this it is necessary to clearly understand the goal

behind a specific policy. This is, the expected end result being brought about

by the application of the policy.

To conclude, support for innovation is key to maintain the European

competitiveness in the global economy. However, not every single policiy or

support programme may be adequate to promote the development of a specific innovation.

Delivering policies capable of effective innovation support require a deep

understanding of the targeted innovation and the factors surrounding it (the Innovation

System). Innovation systems can be analysed, and the results of this analysis

can be particularly helpful for policy makers to understand where the key

barriers are in regard to the development of a specific innovation. Thus, the

results of the analysis will provide policy makers with the right tools to

deliver bespoke and effective policies to support a specific innovation.